Boys wear protective masks as they walk back to their homes after school. PHOTO: AFP

What has Covid-19 taught us about Pakistan’s education system?

This abrupt wake up call should make all the relevant stakeholders reflect upon the future of learning in this country

If someone were to ask me to start a school for online learning, I would have asked them to give us a year to draft a plan for it, get the educators on board, conduct professional development workshops, run some pilots and orient the students and their parents before venturing into it. Yet here we were, transitioning into the digital realm with an array of apps, platforms and software over the weekend as if this was a superpower which we had been secretly harbouring all this time. Hence, as an educator, the onset of Covid-19 has made me reflect upon the purpose of schools and how best they can serve their function during, and after, these trying times.

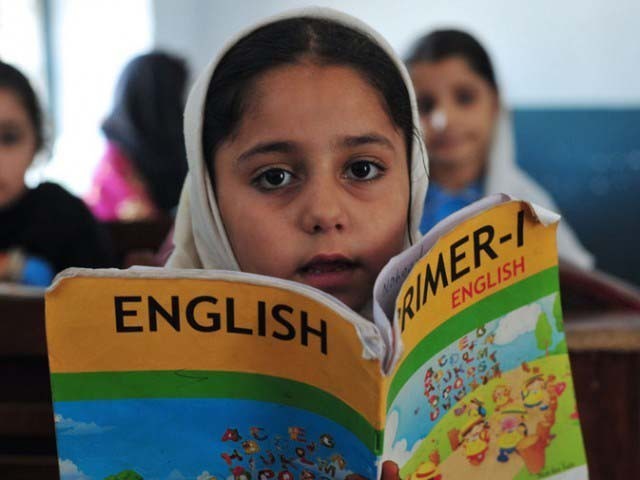

All schools and universities in Pakistan have been closed since March 13th; but before discussing the ramifications of these closures, let’s take a step back and get quick overview of the education milieu of Pakistan. At 22.8 million children, Pakistan has the second largest population of out-of-school children in the world. Unfortunately, those who do go to school aren’t faring too well either. According to the World Bank, 75% of children in Pakistan cannot read or comprehend a simple sentence by the age of 10. Hence the question: what exactly are these children really missing out on during this lockdown? The rest of the 25%, who are attending relatively better public schools, low-cost private schools, middle-tier private schools and high-cost private schools, are now having to grapple with issues stemming from a lack of access to resources during the ongoing lockdown.

For a large majority of these children, access to internet and relevant devices is a luxury that remains beyond the affordability of most families; especially since bringing food to the table has become the primary concern for many as the economy takes a hit. To meet the learning needs of children who are home-bound and do not have access to technology, Pakistan has launched an education channel called “Teleschool”, which aims to air educational content for children belonging to grade 1-12. Undeniably, this is a much needed initiative and is something that should have happened a long time ago. In the long run, it can play a pivotal role in helping the remaining 75% of children have better access to learning facilities, if they are able to employ the right tools (such as using an appropriate regional language of instruction, carefully developed and engaging content, trans-disciplinary learning, civic education, social and emotional learning aspects etc). All of this will take a lot of time to develop but, for now, we can find solace in the fact that is a step in the right direction.

The current crisis has also made it evident that adversity engenders creative solutions. Even for families who do have the needed technology available at home, accessing e-learning holistically remains a privilege reserved for very few in the country because transitioning to the digital medium is something that is beyond the competency of a lot of educators, even those teaching in private schools. While in some institutions educators are trying to build their capacities to make the online shift, in other places students and their parents have been left to their own devices, quite literally, as they access digital learning on their own. Others are relying mainly on their course books to cover the required material, often with the help of their parents. In doing so, a lot of parents are learning about their own potential and abilities to help their child academically, whereas children are learning about their abilities (and in some cases inabilities) to learn independently.

But despite this, the large majority of students in Pakistan are feeling disengaged, alienated and overburdened as educators struggle to cope with the learning curve of various online tools to make sense of this new realm of learning. As a result, a hashtag stating “We reject online learning” was trending on Twitter in Pakistan a few weeks ago. So what does all this tell us about schools as an institution? Evidently, schools are not the only gatekeepers of academic wisdom, as was traditionally believed to be the case. Yet, despite the poor academic standards of many schools in Pakistan, for many they serve as a safe haven away from child labour, child marriages, street violence, and abuse at home. Even in the most dire learning circumstances, schools provide children with positive social interactions which help shape their personalities.

Even in places which have successfully resorted to the most sophisticated e-learning mechanisms, the children are missing out on something. Children learn the best when they are truly engaged; and authentic learning is not limited to memorising a series of definitions and concepts but is an immersive, inquiry-based and context dependent process. Undeniably, students are missing the interactions and connections that were vital for their well-being and growth, primarily because a school is supposed to be so much more than just an academic space. Additionally, across various stratas of society, sending children to school during the day also provides some much-needed relief to the parents, especially the mothers who are often made to simultaneously balance household chores, raise the children, and also manage their own careers.

In some countries where community transmission of the virus has reduced significantly, schools are reopening in phases by employing rotation models which use time and the school space flexibly. This seems like a plausible way forward. Although, it is interesting and ironic to note how the austere measures that are being put in place to protect children from a deadly disease are not very far from their everyday routine in schools i.e. sitting in assigned seats, usually remaining in the same room all day long, walking along a marked track, listening passively to instructions, and enjoying limited time outdoors.

As we teach in the shadow of Covid-19, given Pakistan’s broken education system, us educators need to reflect upon which parts of this system are worth going back to. Do we want to go back to schools where children sit in a room with 30-35 students, tightly packed like sardines in the same spot for six hours a days, passively listening to instructions? Perhaps this lockdown has given us a glimpse at how we can improve our educational institutions to ensure students reap the maximum possible benefits. We can use this as an opportunity to re-design learning spaces/communities, in collaboration with the parents, to further facilitate students’ learning. More than anything, this abrupt wake up call should make all the relevant stakeholders reflect upon the true purpose of schools and the future of learning in this country.

COMMENTS

Comments are moderated and generally will be posted if they are on-topic and not abusive.

For more information, please see our Comments FAQ