Pakistan can’t afford a political crisis during a pandemic

The premier’s conduct has revealed an unyielding attitude at a critical junction in Pakistan's COVID-19 trajectory

Within a fragile and deceptively undulating ‘democratic’ landscape, politics and politicians in Pakistan have consistently maintained a rather adversarial character. In fact, at any given point in the erratic democratic history of the country, all leading national political parties have shown their tenacious adherence to adversarial politics. Perhaps, this is the only kind of mainstream politicking that party leaders are capable of doing in Pakistan. What unraveled in the wake of COVID-19 crisis was no different, a severely adamant inability of the country’s political leadership to conduct consensual politics.

Spain or Senegal, no matter how rich or poor the economy, presently each virus afflicted country has regarded the pandemic as a national or public health emergency, a situation that demands coordination and consensus among leading political institutions and personnel. Akin to national warfare, a state in an emergency subjugates its internal strife and gears all its resources against the enemy. This is the iron law of politics during outbreaks, a law that the centre in Islamabad is unable to abide by. Given the proliferation of positive cases at a breakneck speed, currently the centre has no enemy but the virus itself – a fact best recognised and actualised by the Pakistan Peoples Party (PPP). At this stage, besides a timely development of a medical infrastructure, what warrants recognition is PPP’s unwavering insistence on national and political unity.

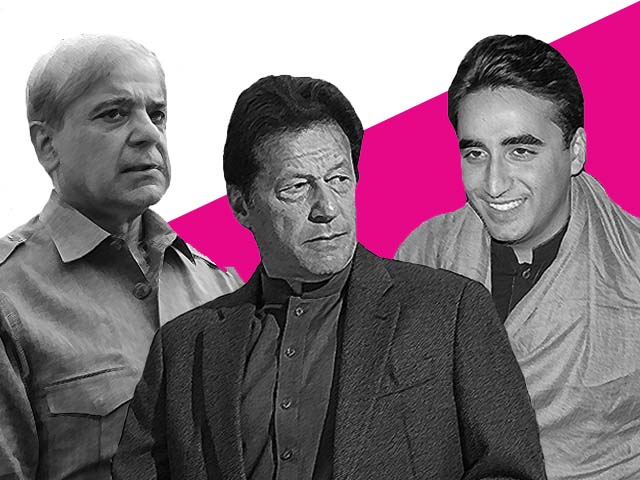

Lately, the crowning feature of party chairperson, Bilawal Bhutto Zardari’s politics has been the suspension of politics itself. From helming a “together we can” hashtag on his tweets to visiting his old political nemesis at Kot Lakhpat Jail, a gesture also well-lauded by Maryam Nawaz, the 31-year-old has successfully taken the lead in eliminating antagonism from the country’s political edifice, an approach praised by most Pakistan Muslim League-Nawaz (PML-N) notables, such as Mushahidullah Khan. Unity of action amongst the country’s numerous political leaderships is not solely PPP’s normative philosophy, it is also a leading strategy and organisational tool to fight coronavirus in Pakistan. The holy grail of the PPP-PML-N block presents a unanimous policy against COVID-19 that should be implemented by concerned authorities within their individual constituencies. What then is hindering or perhaps provoking the consensual politics of the ‘opposition?’

Firstly, the PPP and PML-N political front should not be treated as the opposition. In case of an outbreak emergency, where the traditional parliamentary understanding of an opposition becomes slightly less relevant, an opposition is then the political group speaking against a popular intervention strategy. In the case of Pakistan, the majority, autonomous governments of Sindh and Punjab, as well as the PML-N, have ruled in favour of a lock-down. It is the incumbent government, the Pakistan Tehreek-e-Insaf (PTI), that has now become a rock-ribbed opposition to the popular idea of a lockdown. This reflects the centre’s resolute subscription to the traditional politics of conflict.

Secondly, for any progress on a lockdown strategy, the prime minister’s concerns do become key spoilers. Prime Minister Imran Khan and PTI officials have chosen to speak for the 25% of the population that lives below the poverty line. This is the primary consideration, a rather narrow spotlight, that impedes a political consensus on a complete lockdown. While the parliamentarian ‘Robin Hoods’ continue to oppose prompt, radical measures, correspondingly, the contagion virus continues to steepen the country’s alarmingly combustible trajectory. The question of the nation’s poor, as well as the economic costs of shutting down the country is an important one. It is also a question that has been answered repeatedly by numerous PPP and PML-N leaders and has fallen on either deaf ears or none at all – as seen in case of the Imran Khan’s questionable exit from a critical session with opposition leaders.

Convened by Asad Qaiser, Speaker of the National Assembly, the online parliamentary session was less of a ‘session’ and more of a one-sided address, best suited for an introspective echo chamber rather than a conversation on a national emergency. The prime minister made his exit right after communicating his concerns and stance against a total lockdown. Shahbaz Sharif, leader of the opposition and Bilawal Bhutto, walked out in protest. The implication of such an antagonistic political climate is disastrously consequential. PML-N politician Khawaja Saad Rafique aptly warned against such petty politics and mainstream politicking amidst a crisis, calling it an immoral, inhuman act. His recommendation to the incumbent opposition – to continue striving for consensus – is an important one. Considering that the natural condition of Pakistani politics is to fall in the deathtrap of the politics of antagonism, it is of critical importance that the PPP-PML-N block successfully furnaces cohesion out of chaos.

Sindh Minister for Education and Labour Saeed Ghani, did address the prime minister’s concerns, arguing that Pakistan will also have to bear a hefty but necessary economic cost to avoid a greater economic catastrophe. He highlighted the global economic condition that has taken a sharp downturn. How will the local economy thrive during a recession? This is an important question because unlike PTI’s politics, the national economy does not operate in a vacuum.

Daily wage labourers, who constitute a large chunk of the country’s labour force, would be hit hard in a lockdown situation. Also, as estimated by the Asian Development Bank, Pakistan may incur a minimum loss of $5 billion due to the coronavirus. Although the prime minister’s rationale for opposing a lockdown is well-founded, it does seemingly spectate the crisis through a monochromatic, narrow vision.

Lately, Imran Khan’s office and party notables have been communicating his call for political unity, but it seems to be a poor example of following a political fad – after all when in Rome, one does as the Romans do. At large, in keeping with his popular image, the premier’s recent conduct has revealed an unrelenting, unyielding attitude and Pakistan, at a critical junction of its COVID-19 trajectory, cannot afford this. Communication and flexibility are crucial to consensus politics.

COMMENTS

Comments are moderated and generally will be posted if they are on-topic and not abusive.

For more information, please see our Comments FAQ