Dissecting the political future of PPP

Despite the political pedigree, the problem is that PPP has now lost its appeal among the masses

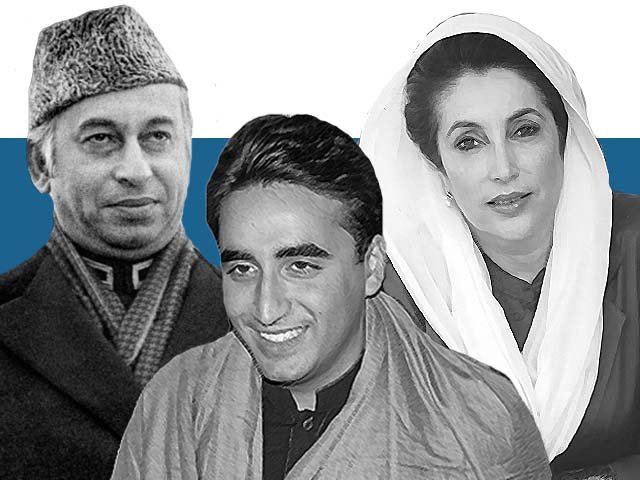

Democracy in Pakistan has never been allowed to flourish and has always been subject to direct and indirect military interventions. The graves of former prime ministers Zulfiqar Ali Bhutto and Benazir Bhutto, and those of their family members buried at Garhi Khuda Baksh, are a testament to the price which the Pakistan Peoples Party (PPP) has paid for taking a stand against the powers that be. However, since the demise of Benazir, the PPP, which once enjoyed a strong vote bank in Punjab and Khyber Pakhtunkhwa (K-P), is not doing so well there during the recent elections. It seems that PPP has now only been limited to the province of Sindh. Initially launched as a far-left centrist socialist party, in its early days PPP was able to garner attention from broad segments of society; from labourers to conservative traders, and from far-left progressives to the far right centrists. Even during the days of General Ziaul Haq, PPP was the party which kept alive the hope that democracy would return to the country. However, despite the political pedigree, the problem is that PPP has now lost its appeal among the masses.

Most blame Asif Ali Zardari for the party becoming a right-wing centrist party when it comes to economic policies and the politics of negotiations. PPP under Zardari has rarely challenged the status quo, and the party’s abysmal governance in Sindh over the years are the reason for its downfall. However, it was Benazir herself who witnessed the end of socialism in the form of the Soviet Union collapsing and watched the influence of Washington and its allies in Islamabad reshape the economic policies of the party. Benazir, after coming to power in 1987 and then being ousted by then-president Ghulam Ishaq Khan, learned her lesson. In her second term as prime minister in 1993 she gradually changed the socialist economic narrative of the party to the centre-right economic narrative. However, Benazir never compromised on the liberal, progressive and social narratives of PPP and, even after her death, the party still remains the only major political party that has no ambiguity when it comes to its progressive and liberal views.

In 2007, when Zardari led the PPP government, the country was in a state of war as terrorist organisations were wreaking havoc across the country. The wave of suicide bomb attacks meant that there was no chance of extensive foreign investments coming into the country. Pervez Musharraf, who created an artificial boom in the economy through the real estate and personal finance sectors, never gave attention to the growing energy crisis. So, when Zardari took charge, Pakistan was witnessing a shortage of electricity and gas. Zardari, however, was unable to concentrate much on the economic turmoil at the time since he was kept busy: first by the lawyers movement for the restoration of judges backed by his political rival Nawaz Sharif, and then he had to focus on saving Pakistan’s face on the foreign front after Osama bin Laden was killed by American forces in Abbottabad. Even though the 18th amendment, in which the PPP along with other parties gave provincial autonomy to the provinces, and the move to finish the article 58-2(b) virtually blocked the chance of direct martial laws, PPP’s performance on the governance front was not satisfactory. Which is why in 2013 PPP’s arch-rivals, the Pakistan Muslim League-Nawaz (PML-N), won a thumping majority in the National Assembly.

The PPP was routed in Punjab and the 2018 elections saw the decline of PPP’s vote bank in Punjab and K-P. The PPP missed the trick by not funding mega infrastructure projects and, even after shunning the socialist economic agenda, the party has never been able to adopt a clear and progressive economic narrative even in the province of Sindh, where it is has been holding dominion for years. The other problem for PPP remains the lack of interaction with the urban youth in Punjab and K-P. PPP also neglected the emergence of social media in both the 2013 and 2018 elections, spending the least amount of money on digital and mainstream media advertisement among the major political parties during the 2018 elections. Nonetheless, initiatives like the Benazir Income Support Programmes (BISP), the setting up of a bone marrow transplantation unit at the Dow University of Health Sciences (DUHS), the allocations of funds for the infrastructure development of Tharparkar, and many other projects are benefitting certain localities in the region.

But the problem remains that all this is happening in interior Sindh where PPP already enjoys popularity. PPP’s biggest challenge is to revive its vote bank in the province of Punjab since that is where the maximum number of seats are in the National Assembly, and losing it means losing the centre. Therefore, Bilawal Bhutto Zardari has a daunting task ahead of him because he needs to somehow create space in Punjab and K-P for his party, where he will be pitted against the likes of Maryam Nawaz and Imran Khan’s Pakistan Tehreek-e-Insaf (PTI). Though, if given a level playing field in the general elections, PPP could manage to win few seats from south Punjab. But that is not enough since PPP, as the only major liberal and progressive centrist party, needs to win over voters in central and northern areas of the region in order to win back the province. This is unlikely since given the anger following the ouster of Sharif many in the province will vote for PML-N in the next general elections.

Thus, Bilawal needs to win support among the youth of urban and rural Punjab. He may not be able to win over many voters in northern and central areas in one fell swoop, but he has to present a strong counter-narrative so that his party candidates at least have a fighting chance in the region. In order to accomplish that, PPP will need to get rid of its old stalwarts and hire a new think tank team and social media wing which understands the dynamics of modern-day politics. As far as K-P is concerned, given the bus rapid transit (BRT) fiasco, PTI is bound to lose support in the province.

PPP can gain a footing in K-P, and the way Bilawal has been taking a stand for the youth with regards to human rights issues in the region is a sign that he will be banking on K-P in the next elections. If PPP can manage to win a dozen National Assembly seats in the next general elections from K-P and another eight to 10 from south Punjab then it can increase its tally of seats to around 65 in the next elections. If PPP is lucky, the Sardars of Balochistan can join its ranks too and boost the party’s tally to 75-80 seats in the National Assembly. That is how PPP can re-emerge in all the provinces of the country as far as electoral politics is concerned. Although this is only a hypothetical calculation, it is possible that PPP takes 75 seats in the next elections, but the party needs to resurrect itself in Punjab if it truly wants to turn the tables. For that to happen, PPP will need to win at least 75 seats so that a coalition government can be formed in the centre and PPP in return can take a few of the portfolios in Punjab, and in the process impress the vote bank there for the next general elections.

This will require a concerted effort from Bilawal to reshape the narrative of PPP in Punjab, which is currently only focused on criticising developmental projects in the province and keeps revolving around the legacy of the Bhutto dynasty. That alone is not enough to earn PPP a growing number of supporters in the province. PPP must understand that it needs to build Bilawal as a brand, like the PML-N did with Sharif and Maryam, or the way PTI did with Imran Khan. The problem with PPP is that they are still selling the Bhutto brand, which has only has a few takers outside of Sindh.

PPP should learn from the mistakes of the Congress party in India, which, despite being a liberal and progressive political party, has lost ground to a far-right extremist party like the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP). PPP needs to pitch Bilawal as a political brand and to do that it needs to convince the centrist right vote bank which forms the majority of the country’s voters that PPP is not a one-dimensional political party, as depicted by its opponents and most media houses. Bilawal needs to shed the old school thought of his party and must inject some fresh blood in the PPP ranks. Despite all the problems within the party, PPP still remains the sole major centrist party which espouses progressive and liberal narratives, and can bring a much-needed end to the growing culture of intolerance in the country.

COMMENTS

Comments are moderated and generally will be posted if they are on-topic and not abusive.

For more information, please see our Comments FAQ