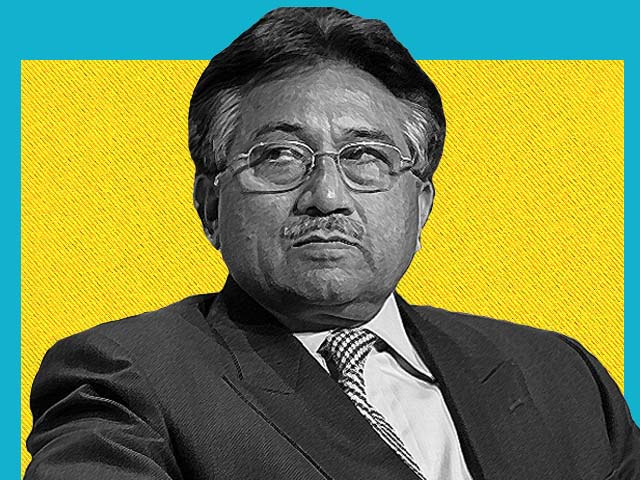

The Musharraf verdict: Of spin doctors and legalities

The retired general's death sentence will go down in the annals of history as an unprecedented judicial decree

The doctrine of necessity refuses to go away. It is something of an extra constitutional anomaly which acts as a panacea for a whole host of unconstitutional acts and illegalities. Wherever logic fails, this doctrine comes to the fore. It gives legitimacy to unconstitutional acts, allowing the judiciary to compromise with the deep state in order to surrender institutional independence.

Chief Justice Muhammad Munir sowed the seeds of this notorious doctrine in the Molvi Tameez-ud-Din case when he ruled that it was the governor general who was sovereign, not the general assembly and ever since then, it has deeply rooted itself in the judicial consciousness. Every once in a while, an effort is made to uproot it. However, it refuses to give way to the rule of law and constitution.

The special court was established under the Criminal Law Amendment (Special Court) Act in conjunction with Article 6 of the Constitution and the High Treason (Punishment) Act, 1976. When two of the court's judges, namely Justice Waqar Ahmed Seth and Justice Shahid Karim decreed that Pervez Musharraf was guilty, it was thought in some legal circles that the door to coup d'état or a military coup had finally been shut. However, paragraph 66 of the judgment delivered by Justice Seth, which proposed hanging the former chief of army staff's corpse publicly, gave Musharraf sympathisers an excuse to malign both the judge and the ruling in order to turn attention away from the content of the other 65 paragraphs. A fiery press conference was held by the government thereafter where they expressed the intention to file a reference under Article 209 of the Constitution before the Supreme Judicial Council against Justice Seth.

There are four main arguments put forward by Musharraf's apologists. These need to be dealt with one by one.

The first and foremost argument is that since the cabinet's approval was not sought by then prime minister Nawaz Sharif, the formation of the special court was unconstitutional. The fallacy in the logic of this argument is self-evident, especially since the requirement to obtain the cabinet's approval on such matters was made mandatory by the Supreme Court three years after the formation of the special court. It is well-settled law that judgments of the superior courts are to be applied prospectively. Therefore, a new ruling can only be applied on the cases that follow it and not on those matters which precede it. Simply put, legislation and judicial precedents do not operate retrospectively. Therefore, the rationale laid down in the Mustafa Impex case (PLD 2016 SC 808), which directs the prime minister to obtain the approval of the whole cabinet before making an order or decision, is being used fallaciously and is not applicable to the Musharraf case.

The second argument made is that since Musharraf, through the Provisional Constitution Order, held the constitution “in abeyance,” he cannot be prosecuted under Article 6 because when Musharraf imposed the emergency in 2007, the words “hold in abeyance” and “suspension” were not part of article's text and these terms were included after the 18th amendment was passed in 2010. Before the wording was changed, alleged offenders could only be prosecuted under article 6 if they had subverted or abrogated the constitution. Mushrraf supporters argue that, as per article 12(1) of the constitution which offers protection against retrospective punishment i.e. punishing crimes which at the time of the act were not illegal, the former military dictator cannot be tried under article 6 because suspending the constitution was not an illegal act in 2007.

However, clause two of Article 12 in no uncertain terms states that clause one shall not apply to any law making acts of abrogation or subversion of a constitution. Therefore, article 12 does not offer protection against retrospective punishment if the alleged offender is guilty of crimes against the constitution. Justice Karim in his elaborate judgment, shines a light on it in paragraph number 50, stating that clause two carves out an exception to the right against retroactive punishment because those committing treason cannot be allowed to go scot-free, even if it is applied ex post facto i.e. retrospectively.

In any case, the phrase 'hold in abeyance' was purposefully used when emergency was imposed on November 3, 2007, to try and circumvent potential repercussions under Article 6. However, it was merely mischievous word play. The Sindh High Court Bar Association case (PLD 2009 SC 879) shined a detailed light on the phraseology used in Article 6 and stated that "hold in abeyance" is tantamount to the subversion of the constitution.

The third argument put forward is that Musharraf was not afforded the right of due process enshrined in Article 10-A of the constitution, as his trial was held in absentia i.e. in his absence. This argument would have been tenable and valid, had Musharraf not been present in the court at the time of framing of charge. He was physically present in court when the charge was read to him on February 18, 2014, as is evident from a perusal of paragraph No 13 of the judgment authored by Justice Seth. He pleaded not guilty on all five counts, highlighting his desire to stand trial. His counsel, Farogh Naseem, the incumbent law minister, cross-examined the witnesses for days on end. Additionally, the verdict was announced after six long years.

In short, the requirements of due process such as an opportunity to produce evidence, to cross-examine and to be represented by a counsel were fully satisfied. This argument put forward by Musharraf’s supporters is further diluted by the Supreme Court in its judgment of 2019, namely SCMR 1029 Lahore High Court BR Association V General (R) Musharraf where the special court was directed to proceed with the trial in his absence in view of Section 9 of the Criminal Law Amendment (Special Court) Act, 1976 which clearly states that no trial shall be adjourned by reason of absence. The judgement and the article has been referred to in paragraph 44 of the special court verdict. It was further held that proceeding with the case in the defendant’s absence would not contravene Article 10-A of the Constitution, as the trial could not be left to the mercy of the accused.

The fourth argument that is put forth, is that the case built by the prosecution suffered from an inordinate delay of over five years from the date of the alleged offence and the initiation of proceedings. Perhaps this is an attempt to invoke statutory limitation which essentially bars a case from being prosecuted if a certain amount of time has been passed. Therefore, the prosecution may argue that since six years had elapsed between the imposition of the emergency in 2007 and when the special court was initially formed in 2013, the matter should be time barred.

However, it is important to remember that the law of limitation is not applicable to the constitutional offence envisaged under Article 6 by the legislature. Had it been the intention of the legislature, it would have inserted a provision to this effect. Therefore, the objection raised by Musharraf's side is untenable and unsound. Even if this argument was to be given some credence, criminal jurisprudence generally does not stop the criminal justice machinery from coming into motion solely based on a delay in proceedings.

The moment the special court delivered the judgment, convicting Musharraf of high treason and sentencing him to death, it became functus officio i.e. no longer functional because its mandate had expired. It stood disbanded and became defunct. In other words, the proverbial Rubicon was crossed. There was no going back. As a result, Musharraf has only one legal remedy, that is, to file an appeal before the Supreme Court.

In the wake of this verdict, a petition under Article 199 of the constitution which challenged the formation of the special court pending adjudication before the Lahore High Court (LHC) was rendered infructuous for all intents and purposes. The LHC should have stayed its hand and not assumed jurisdiction to hear and eventually make a decision on the petition. However, like several previous instances, this too proved to be a classic case of putting the cart before the horse.

The question arises; can the high court sit in judgment over the orders of the Supreme Court? The answer is obviously negative. The Supreme Court settled all the subtle legal questions facing the special court leaving no doubts about its legal existence.

One can be forgiven for feeling that in order to provide Musharraf speedy justice, the LHC judgment has ultimately left jurisprudence in tatters and turned settled law on its head . Musharraf's counsel adopted a circuitous route in order to get his conviction overturned and declare the formation of the special court ultra vires i.e. legally invalid, failing to realise that it is a well-entrenched law that an appeal is a continuation of the trial and therefore, all factual and legal controversies shall be reopened during its course which will give Musharraf ample opportunity to defend himself.

It is simply baffling that, where an option of legal recourse had already been provided, the high court chose to entertain, hear and adjudicate the petition. Now that an appeal has been filed in the Supreme Court by Musharraf’s counsel as a precautionary measure as well, one earnestly hopes that the apex court will hold aloft the banner of the rule of law. A review has also been filed in the LHC against the decision passed by the three-judge bench, lead by Justice Naqvi.

In summation, Musharraf's death sentence will go down in the annals of history as an unprecedented judicial decree. It was a leap forward in the right direction. Conversely, the LHC judgment in this regard will go a long way towards further cementing the doctrine of necessity. It is essentially legal regression. Therefore, it would appear that the independence of the judiciary and the ruling elite being brought to justice are both elusive dreams. It is now clear that it is not the judiciary which is independent as a whole, but merely a handful of strong-willed judges, who are willing to go against the grain in order to uphold the constitution and the rule of law.

COMMENTS

Comments are moderated and generally will be posted if they are on-topic and not abusive.

For more information, please see our Comments FAQ