One of the relatively well-preserved Buddhist sites, its position on a hill top saved it from successive invasions. PHOTO: TAYEBA BATOOL

Preserving Takht-i-Bahi: why the old and the new must walk hand in hand

The community’s ownership and affiliation with the place has been marred by state-led interventions

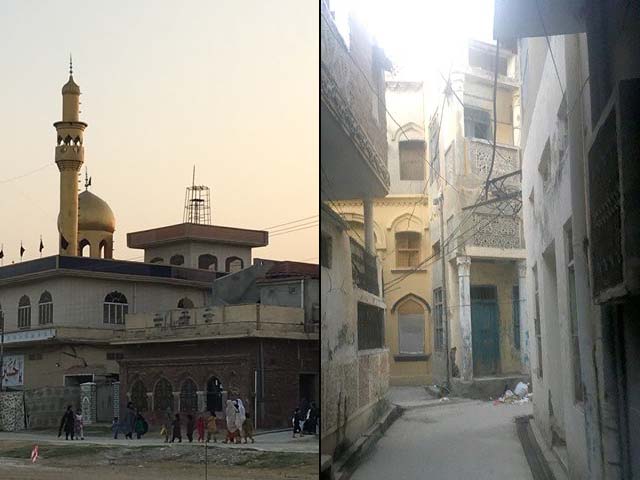

Before arriving at the historic ruins of Takht-i-Bahi (also called Takh’ Bahi), a former Buddhist monastic complex and an Indo-Parthian archaeological site, one passes through its namesake village. A narrow and fractured two-way road snakes through, with shops on either side, offering consumer and plastic goods. Quite unfortunately, there are no hints or traces of the village’s shared history, pride or even association to the neighbouring site’s religious, historic and cultural significance.

Instead, open drains, unregulated parking, hanging wires, peeled paint strips and half-torn posters on buildings are a common sight that greet visitors.

Photo: Tayeba Batool

Photo: Tayeba Batool Ruins of the Buddhist monastic complex of Takht-i-Bahi. Photo: Getty

Ruins of the Buddhist monastic complex of Takht-i-Bahi. Photo: GettyPerhaps the villagers are not looking to welcome outsiders. Or possibly they are unaware of Takht-i-Bahi’s significance. A UNESCO World Heritage Site, this complex was built in the first century, and is an important relic of Pakistan’s Gandhara region. The name is said to be derived from Persian, where 'Takht' means throne and 'Bahi' means water (referring to the water sources on the mountain top). One of the relatively well-preserved Buddhist sites, its position on a hill top saved it from successive invasions. However, several of its artifacts, recovered during earlier excavations, are either lost to smuggling or can be found in the British Museum now.

Statuettes from Takht-i-Bahi, from the British Musuem’s collection. Photo: Getty

Statuettes from Takht-i-Bahi, from the British Musuem’s collection. Photo: Getty Photo: Tayeba Batool

Photo: Tayeba BatoolFor the government, any restoration work (genuine or not) is deemed complete once the physical uplift has followed through. Economic opportunities, in the form of employment creation, are hailed as gains for the whole community. Tourism is increasingly evolving and becoming more enterprising, allowing the creation of jobs such as tour guides, ticket collectors, security personnel and cleaning staff. However, there are still constraints with regards to gender inclusion, an English bias, income enhancement, and nepotism.

While the economic approach for heritage management needs closer scrutiny, another important aspect is the highly sought after element of sustainability. What happens once the refurbishment is complete? Despite being enlisted as state property, who are the real guardians? In the case of Takht-i-Bahi, the site is covered on at least two sides by the village. Access to the road is through the village, and it is this community which leads us to this wonderful remnant of history. Thus, is the village responsible for Takht-i-Bahi’s sustenance?

Photo: Tayeba Batool

Photo: Tayeba Batool Photo: Tayeba Batool

Photo: Tayeba Batool Photo: Tayeba Batool

Photo: Tayeba BatoolThe community’s ownership and affiliation with the place has been marred by state-led interventions for the site’s archaeological management, while ignoring its social fabric. Not taking the site’s social framework into consideration is a pressing issue that isn’t discussed enough in archaeological management, site rehabilitation, and rural/urban development. Historical sites and physical heritage are assumed to be a shared national asset, which are preserved and managed by designated authorities. These authorities have structures set in place that are inherited from our colonial legacy. Neither visited nor reformed since independence, these structures do not include the simple element of inclusion. By excluding the community, the social infrastructure woven within the physical environment is dismissed.

Under the current lamentable state of public education and the national curriculum, which denies any non-Islamic archaeological history as being part of the nation’s inheritance, there are always questions about heritage and cultural identity. However, what is known is that historic sites in Pakistan are not always left abandoned, isolated, or forgotten. In the neighbourhoods of the walled cities of Lahore, Peshawar and Multan, people continue to interact with these ancient sites. A sense of ownership and identity evolves in the microcosm of the surrounding community and that is where all interventions have to start.

Photo: Tayeba Batool

Photo: Tayeba Batool Photo: Tayeba Batool

Photo: Tayeba BatoolEven before the physical intervention, financing and project launch, conservation has to account for the people in the region to ensure a sustainable effort at uplifting the heritage site. This implies that community leaders and residents are consulted and granted the right to own equal stakes in the execution of the project. Sometimes, it will also necessitate an assessment of not only the perimeters of the heritage site, but also of the adjoining community area, to realise how refurbishing one can improve the other. To some extent, this has been the aim behind renovating various neighbourhoods inside the Delhi Gate, as part of the conservation efforts in the walled city of Lahore.

In 2011, a master plan for the conservation of Takht-i-Bahi and the neighbouring city was prepared, with an anticipated implementation from 2012-2017. As part of the review of the site’s boundaries, the entire mountain area was declared an “archeological reserve” by the state authority in charge, which is the government of Khyber Pakhtunkhwa (K-P). The presence of barbed wires and fences could potentially deter illegal diggers or miscreants, but it also signals a strong boundary which isolates the community, not allowing them to engage or intersperse with the historic space. Urbanisation and land regulation need to be reconciled in a framework that does not isolate the community.

Photo: Tayeba Batool

Photo: Tayeba Batool Photo: Tayeba Batool

Photo: Tayeba BatoolExpanding heritage or archaeological management to include urban management or rural development is not an easy task. It will need the engagement of multiple stakeholders within the government and private sector, along with the community. But additionally, it will also require multiple disciplines to be involved, such as architecture, urban/regional planning, historic preservation, economics, and anthropology. Social sciences are the key to understanding the transformations in the area and ensuring that ground realities are taken into account at every step of the decision-making process.

Without this major shift in thinking about heritage management, state-led planning will continue to operate inefficiently, and upcoming generations will be deprived of important markers that characterise this country, such as Takht-i-Bahi.

COMMENTS

Comments are moderated and generally will be posted if they are on-topic and not abusive.

For more information, please see our Comments FAQ