Our guide is my granduncle who resides in the UK but visits his hometown every year, relishing in the simplicity of the place and reminiscing his childhood memories. PHOTO: TAYEBA BATOOL

A walk through the historic streets of Chakwal

I am struck by the confluence of the old and the new, and how it changes within a matter of minutes & just a few feet.

We start our journey on foot from the doorways of our ancestral home on Allah Da’d street, located across from Sarpak (meaning ‘pure ground’ in Urdu). I visit Chakwal occassionally and we always spend a few days in this house, owned and originally built by my great-great-grandfather.

The baithak in the centre commands serenity and space, and brings all the members of the household together for communal dining and reminiscing of the past. The surrounding rooms have changed shape over the years and have adapted to modern day comforts, but the elders still remember how everything was originally, comprising of: a space to keep cows and hens, an open kitchen, and, a raised platform for prayer.

The real joy of visiting a place is always in what lies beyond the walls. We exit the gates to emerge onto the street, facing Sarpak. A few decades ago, this was a rain-filled pit that had water clean enough to bathe or wash clothes. Later, it became the bathing and resting ground for buffaloes before resigning to its present-day fate of being a garbage dump and algae colony.

Sarpak.

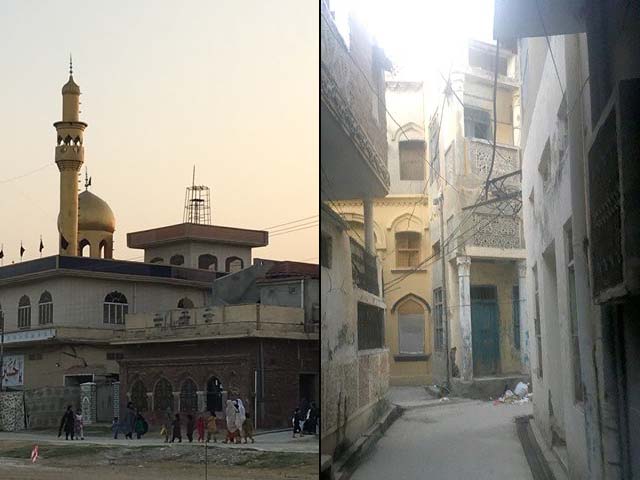

Sarpak.In contemporary times, Sarpak is most closely associated with the Markazi Imambargah close by, and the adjoining huge communal ground. This ground serves multiple functions, such as acting as a cricket ground, a football field, a car park, a shortcut for passing rickshaws and cars, a procession gathering spot (religious or political) and an open idle space to pass the time.

Markazi Imambargah.

Markazi Imambargah.Our guide is my granduncle who resides in the United Kingdom but visits his hometown every year, relishing in the simplicity of the place and reminiscing his childhood memories. His stories relate the transformations of the buildings, the town and the people who used to reside in this neighbourhood.

After crossing the now-metalled road, he quickly leads us onto the sheltered labyrinthine streets (or galliyan) of Chakwal’s oldest parts. The streets are barely wide enough for three people to walk side-by-side, yet motorcyclists pass by, barely breaking speed and almost always (miraculously) causing no harm.

Streets in the old parts of Chakwal.

Streets in the old parts of Chakwal.Gravel and concrete have replaced the older mud paths and narrow water drains lie exposed on either side. The streets are narrow but take a 360-degree turn, and history appears to call out to us at each step.

Traditional handcrafted wooden doorways are still in use, bringing alive the craftsmanship and naturalistic designs of yester-years. Overhead balconies (jharokas) and raised platforms outside the home (takhts) testify how once upon a time all neighbourhood gossip was delivered via evenings spent with neighbours.

‘Jali’ work on the balconies.

‘Jali’ work on the balconies.Arabesque lattice patterns, and arches on windows are yet another reminder of days gone by. I cannot help but notice the similarity here with some of the streets in the walled city of Lahore.

As we walk ahead, we notice that there are no name plates or numbers outside several houses. My granduncle points to multi-storey houses on the way, and relates generational stories of how families residing here, prospered or decayed.

“That is the kothi of the halwai (maker of halwa, which is a South Asian dessert). I met his son in the United Kingdom. One day, this fine, young gentleman comes to my office looking for me, and announces, without shame, that he was the son of the halwai in our neighbourhood. He has really helped his family back home.”

This is one of the many rags-to-riches stories to be encountered in this region. Several prominent businessmen, high ranking military personnel, and politicians can trace their roots to Chakwal – both the town and the villages within its judicial boundaries.

My granduncle also points out a marker on our path saying:

“Every year I visit, I always see trash dumped at this exact spot. Always. I don’t know why.”

The mound of plastic bags, food waste and fruit peels on the otherwise clean alley is an eyesore and is disturbing for the olfactory senses. The mystery of how it gathers here, who collects it and why it is not removed by the residents is still unresolved. Unfortunately, this menace of waste pollutes much of our interaction with the urban space.

A little further, we arrive at a tile clad wall and a dome structure, hinting that we were standing before a mosque.

“Can you guess how old this mosque is?”

Our guide eyes us eagerly, anticipating the ‘wow’ moment to come.

“Sometime around 1950?” I suggest.

“This is the oldest mosque in Chakwal, almost three centuries old,” he informs us.

And we are, as he expected, awe-struck standing in front of the Paki Masjid. The mosque was established in the beginning of the 17th century, soon after the era of the last Mughal Emperor, Aurangzeb. The plaque on the wall also claims that a certain Chaudhary Guda Baig Khan laid the mosque’s foundation.

The oldest mosque in Chakwal.

The oldest mosque in Chakwal.After multiple turns through the residential quarters, we come out into Bhabra Bazaar, the market place. I can see stalls and carts selling fruits, vegetables, Chinese plastic toys, clothing items, and savoury snacks such as chana chaat, dahi bhallay, and french fries are lined up. Sound levels here have increased manifold. The traffic din from the main road further ahead, fills up the space, alongside the conversational Punjabi and the street hawkers loudly declaring goods for sale.

I also spot the Bab-e-Chakwal (Gate of Chakwal), a recently constructed monument, at the end of the line. I am struck by the confluence of the old and the new, and how it changes within just a matter of minutes and just a few feet. The hanging bulbs on the stalls are already lit. The brightest point, however, is the shop in the middle: Chakwal’s famous ‘Pehlwan Rewari’.

“This is the original and very first shop,” another long-time denizen of Chakwal tells me.

Multi-coloured fairy lights decorate the signboard, with the trademark photo of a man with a moustache (possibly the Pehlwan who started the business). The rewari (sweet candies traditionally made of ghee, gur and sesame seeds) is a speciality of Chakwal, as the sohan halwa is to Multan.

Chakwal’s famous ‘Pehlwan Rewari’.

Chakwal’s famous ‘Pehlwan Rewari’.Emerging onto the main Chakwal Road, I already feel nostalgic for the more intimate, accessible space we were walking through. Cars are now in sight, as are billboards, stretches of multi-storey buildings, and a big, grey road leading to (or coming from) a vast stretch of land. At a small flower market on the main road, my companions buy rose petals for their visit to the graveyard the next day.

We return via the Hospital Road, behind the District Hospital, which was established during colonial times. Passing by a traditional tandoor, we grab fresh, hot naans for the journey back. My granduncle introduces us to one of his class fellows, a fruit seller, who insists we take home a few oranges.

And that is how the walk through history ends – reaffirming bonds of friendship, memories and places, and a social fabric that keeps everyone together, even after so many years.

All photos: Tayeba Batool

COMMENTS

Comments are moderated and generally will be posted if they are on-topic and not abusive.

For more information, please see our Comments FAQ