Sensationalism over ethics, what happened to journalism?

We see the use of images that tend to sensationalise issues that demand a more sober and serious discourse.

A picture is worth a thousand words, but what if those words are untrue or misrepresent the truth? From the time print journalism made its advent, news organisations have realised the importance of the supplementary support offered to text by an image, even if it had to be a sketch or a caricature.

However, with the development of photojournalism as a niche field, imagery started competing for space with words to tell a story. Sometimes, pictures told the whole story, whilst others complemented a story by supporting, embellishing and enhancing it.

Things went out of synch when the editorial staff’s choice of the images corresponding to the words of the story either did not gel well or was seen as an attempt to deliberately mislead the readers. The question arose whether the latter was the case or was the editorial desk becoming ‘advertising’ savvy and using the image as bait to lure readers into reading the text. It has, after all, proven to work.

A powerful, even a provocative bordering on the controversial image will definitely capture the reader’s attention. And if the word play around it is cleverly crafted, it will retain one’s attention long enough to ‘induce trial’, according to another advertising jargon, which would lead the reader to read the article to know more about what the image is all about.

But what if the image is not even remotely related to what the article is about. What if it somehow conveys the meaning quite opposite to the one intended by the writer? Does that then become offensive?

Yes it does.

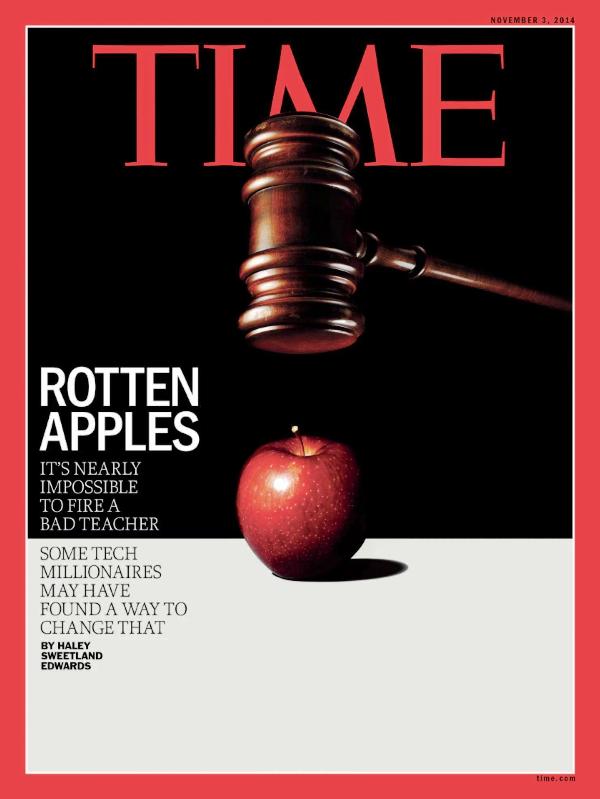

The recent reaction to a cover story of Time magazine, which was covering the protests of teachers across the US on regulations that would have impacted them negatively, is just one of the examples.

Photo: Time Magazine

Photo: Time MagazineThe picture of a gavel coming down hard on an apple along with the caption,

“Rotten Apples: It’s nearly impossible to fire a bad teacher. Some tech millionaires may have found a way to change that”.

This immediately gave a negative impression, especially the word ‘rotten’, about the teachers present in the American school system, and the gavel trying to smash the apple portrays that a harsh response is required to tackle the issue.

In reality, the article was actually eulogising the role of good teachers and discussed the notion that just because of a few bad teachers present in the system, the entire system should not be subjected to legislation. The article’s main purpose was to portray teachers in a good, positive light. But the message that the cover ended up portraying was that there are loads of “rotten apples” (bad teachers) that only “tech millionaires” know how to remove from the classroom.

As expected, in this day and age of instant feedback, the cover received immense backlash and criticism. The teachers, in particular, were furious at the cover. The American Federation of Teachers, the second largest teachers union in the US, started a petition demanding the magazine to apologise to teachers for its misleading cover when compared to the article itself. The petition stated,

“The cover is particularly disappointing because the articles inside the magazine present a much more balanced view of the issue. But for millions of Americans, all they’ll see is the cover and a misleading attack on teachers.”

Similarly, in our publications, we see the use of pictures and images that tend to sensationalise issues that demand a more sober and serious discourse. This of course varies in degrees. The above example is of giving a negative spin to a positive discussion. We also have imagery which discriminates and trivialises.

For instance, pictures of people appreciating art pieces at an exhibition, without showing the artist or their work. This is especially jarring when the article accompanying the picture is totally focused on the work of the artist.

Discrimination or exploitation arises when a violence or disaster victim’s right to privacy is wantonly flouted, putting them at further risk within their communities. Of course, then there are some instances where images are totally unrelated to the text. There will be a picture of a starved child when the article is about child education.

Closer to home, in the event of a disaster, even a slow moving one like the one being faced by the people of Tharparkar, misrepresented imagery lowers the credibility of the written text accompanying it. Desk reports when mentioning the drought carry pictures of a parched landscape, which is completely unlike the reality in Tharparkar, which is a desert. So while the problem is very real, the imagery serves to dilute, rather than strengthen the impact of the message.

We also have the editorial staff pulling out stock pictures in the event of a blast or an attack and showing bloodied people. But if looked closely, it can be discerned that the images do not have any connection with the location or the story. This again serves to lower the credibility of the media that is indulging in these practises.

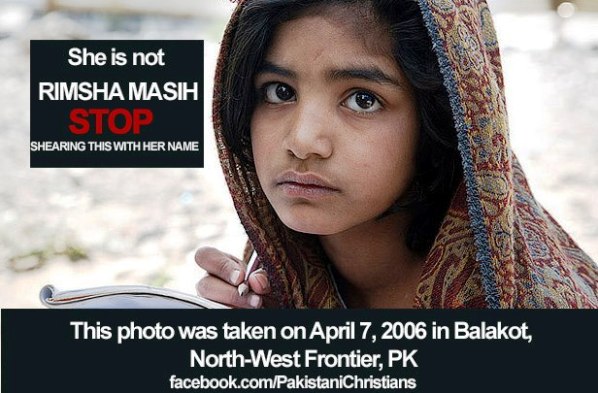

On another media, which has an immediate multiplier effect – social media, we see this happening a lot more, and not just from random personal accounts but from media houses. We have had people posting a picture of a very scared looking girl when garnering support for Rimsha Masih when she was undergoing the ordeal of the blasphemy accusations. When it was revealed that the picture was not hers’, it actually damaged the campaign for her support.

Source: Pakistani Christians Facebook page

Source: Pakistani Christians Facebook pageYet another example is the attempt to bring to attention the atrocities being perpetrated on the Rohingya minority by the Buddhist monks in Myanmar. The pictures that were used were of unrelated events that had taken place at another time and place.

In a competing landscape, media practitioners need to remember that truth will ultimately come out. Not too long ago, we had the picture of a four-year-old Syrian boy separated from his family in the desert. This gained a lot of traction on the social media but soon the truth emerged that he had not actually been separated.

Here 4 year old Marwan, who was temporarily separated from his family, is assisted by UNHCR staff to cross #Jordan pic.twitter.com/w4s2mrNnMY

— Andrew Harper (@And_Harper) February 16, 2014

Why does this happen? Is it because of a deliberate angle, lack of ethics, or poor editorial oversight? It could be any or all of the above.

There was a time when the person editing the article was also responsible for sifting and sorting the images to pull out the most appropriate one to complement it. Now, many times, one gets the impression that the images are being chosen without any great comprehension of the written words.

Whatever the reason, one fact editorial desks need to be wary of is, whether it is a careless oversight or a deliberate misrepresentation of the facts, reaction to such instances will be swift, and may serve in a loss of audience. This would actually run contrary to the objective of gaining attention of more and more people through ‘powerful’ imagery.

So the back-to-basics approach of finding balance and connection between the words and pictures will serve any publication, or even an online forum, rather well in the long run rather than opting for sensationalism that may get the eyeballs, but not the appreciation.

COMMENTS (8)

Comments are moderated and generally will be posted if they are on-topic and not abusive.

For more information, please see our Comments FAQ