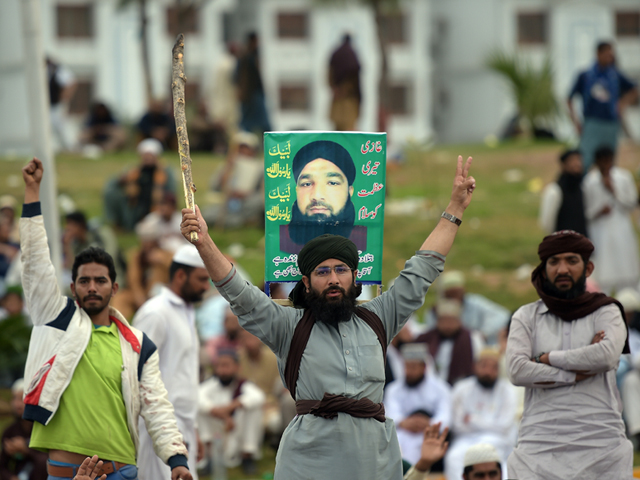

Supporters of executed Islamist Mumtaz Qadri shout slogans during an anti-government protest in front of the parliament building in Islamabad on March 28, 2016. PHOTO: AFP

The world will judge Islam by the way Muslims behave in the name of Islam

In a society where Ilmuddin is considered a legend and a “shaheed”, Taseer’s murder was hardly surprising.

A year ago, the government took a bold decision by hanging Mumtaz Qadri, the murderer of late Salman Taseer. The funeral, despite the media’s lack of coverage, was attended by thousands of people, highlighting the appeal of a man who was nothing but a murderer. One year later, thousands of hardliners defied the rally ban to attend his first death anniversary.

The sad reality is that for many, Qadri is a hero, and the significant percentage of those who disagree with his actions have an “empathetic” attitude towards him. I have heard people coming up with all kinds of justifications for Taseer’s murder, to such an extent that people believe Taseer was actually guilty and punishable by law, and since the justice system in Pakistan is corrupt and implementation of laws is derisory, Qadri had no other option but to take matter in his own hands.

A year ago, one of my friends shared a picture of Qadri’s funeral on social media and claimed that people like him were a minority as fanatics had outnumbered “moderates”. A year later, he was openly stating that the abducted bloggers were all blasphemers and therefore should be killed. He was willing to believe it all because certain TV anchors were favouring the notion. The fact that there was never any irrefutable proof showing they had indulged in blasphemy escaped his otherwise rich imagination.

It can be easily fathomed that the difference between him and Qadri supporters is merely of social class and perhaps in the belief about who they think is guilty of blasphemy. The basic thought process connecting the two is the same. My friend, who comes from a privileged background, will most likely avoid killing someone directly. After all, he loves his comfortable lifestyle, high salary and also his new-found rediscovery of religion. To take the ultimate “plunge” is difficult for him, but his thinking is clearly supportive of harsh punishments, even if an extrajudicial process is adopted.

Qadri is not merely an individual; he symbolises a mentality, various forms of which are extremely pervasive. A tiny minority is even ready to kill, while others are either supportive of such killers or are supportive of the basic idea that alleged blasphemers should be killed even without a fair trial.

But the disturbing question that lingers is why some people are ready to even resort to killing? Why did Qadri kill Taseer? And why is this “empathetic” behaviour so common in our country? Why are some quarters practising tolerance while the remaining believe in extreme veneration for such acts?

To some extent, the reason behind Taseer’s murder was the extreme reverence attached to religion and the Prophet (pbuh). Outright religious fanaticism is obviously responsible here and perhaps the only cure in the long run is desensitising people from religion. For sanity’s sake, I will not dispute this obvious reality.

But this only partially explains the complex situation. Reverence alone does not lead men to commit murder. It is what society explicitly or implicitly expects with respect to actual demonstration of veneration – particularly when the revered figures and symbols are perceived to be under attack – which often leads to adoption of a particular action. These expectations are not always spelled out clearly but nevertheless articulated through loaded slogans and narratives which project some real life individuals as heroes and villains.

Due to extremely pervasive and loaded slogans such as the one mentioned above, people actually believe that the Prophet’s (pbuh) honour should be protected even if one has to give their life for the cause. Slogans such as these become extremely dangerous with respect to their potential impact. I am not saying that they affect every person in the same way, but it merely takes one individual to get affected in “that” way to do the unthinkable.

Moreover, such slogans and related literature also lowers the threshold of the desired level of “reverence”, as the line for what constitutes as blasphemy becomes blurred and is then left at the individual’s behest as to what they consider blasphemous.

I think this is important because such acts are often committed for personal glorification which society is willing to bestow on such individuals. Yes, Qadri courted possible death when he fired upon Taseer but he also looked towards widespread hero adoration and “immortality’ in the similar vein of Ilmuddin, a hero for some Muslims and a man revered by Allama Iqbal for killing a Hindu in 1929 who had published a supposedly blasphemous book which had contained derogatory remarks about the Prophet (pbuh). He was tried in court and hanged but achieved a legendary status overtime.

In a society where Ilmuddin has been made into a legend and a “shaheed” (martyr), Taseer’s murder and its endorsement or even apologetic defence are hardly surprising. Qadri, in his head, was going to heaven and was on his way to attaining the same legendary status when he took it upon himself to end Taseer’s life, despite the fact that the latter had only asked for a presidential pardon of an illiterate woman accused of blasphemy. And the subsequent showering of rose petals and roaring applause demonstrated that he was not wrong in his calculations. His death, funeral and continuation of that adulation also show that he was not wrong about his legacy.

Today, his mind-set dominates Pakistan and the atmosphere has become so charged that merely accusing someone of blasphemy on social media is enough to pronounce him guilty in the public eye. People don’t even want to know whether the accused actually committed the crime or not as they simply believe the accusation and start demanding blood.

We need to re-examine the narratives about people like Ilmuddin; why do we narrate the story of men like him in a consecrated manner? Why do we glorify violence through such stories? We forget that the world is judging us through our acts. When a sizeable number of us act like this, then the world will doubt our claim that Muslims are peaceful.

In the end, I would like to make a humble plea to all my Muslim brothers and sisters. When you kill or endorse such acts in the name of Prophet Muhammad (pbuh), you are portraying Islam and his legacy in an extremely wrong manner. The world will, and in fact already is, judging Islam by the way Muslims behave in the name of Islam. If we want the world to consider Islam as a peaceful religion then remember to act accordingly. Being violent, endorsing violence, providing apologetic defence for violence and then also demanding that the world should not “stereotype” Muslims and consider Islam as a religion of peace will definitely not work.

COMMENTS (68)

Comments are moderated and generally will be posted if they are on-topic and not abusive.

For more information, please see our Comments FAQ