Urdu and I: A love affair

Urdu welcomed me and I couldn't fathom why I had let go of the language that taught me to express myself eloquently.

In grade six, I handwrote Ibne Insha’s “Kal Chaudvin Ki Raat Thee” and gave it to a girl I firmly believed to be my soul mate. Her lack of enthusiasm at replying with an equally moving ghazal (or even replying at all) dismayed me so I delved further into Urdu literature than I had ever before.

“What was a grade six student doing reading Ibne Insha?” I hear you ask.

To put matters in perspective, I had grown up in a house full of books. I carried my Famous Five right next to Inspector Jamshed and His Gang. Books on history and Islam happened to be the easiest to access and were my first scalps. Daily subscriptions of newspapers Dawn and Jang ensured access to further reading material and Young World and Akhbar-e-Jahan became weekly fixtures. Reading the news paved way for an interest in politics and gradually it evolved into a taste for satire.

Thus, I came across Ibne Insha’s Urdu ki Aakhri Kitab. The vocabulary was like nothing I had ever read before so my parents bought me a Ferozul Lughat (popular Urdu dictionary) to help me understand. I fell in love and there was no looking back. Shafeequr Rahman, Dr Younis Butt and Patras Bokhari became friends that narrated wonderful tales to me. Once I had devoured as much satire as I possibly could, I ventured into the poetry collection in our house.

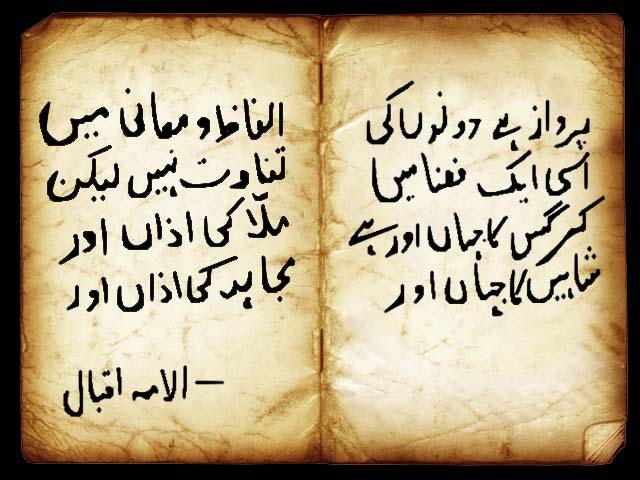

I felt confident enough to finally give these thick books with yellow pages a try. Faiz Ahmed Faiz and Perveen Shakir were the first poets I read. Soon, I added Ibne Insha, Ghalib, Mir Taqi Mir, Iqbal, Mir Anis and Ahmad Faraz to the list.

Since we study Urdu only as a second language under the O’ Level system, I aced my exam with ease and once A’ Level rolled around, Urdu got neglected, pushed aside and forgotten.

Two years later I packed my bags and headed to Toronto for university. Written Urdu had long been cast aside and now it was spoken Urdu that suffered the same fate. English was the global language, I reasoned, and soon I would have no use for Urdu in my daily life.

Much as I try to rationalise that piece of thinking, I cannot anymore.

I finished school in April 2012 and moved soon after to Saskatoon, Saskatchewan. It was here, in a new town, that I discovered how much I missed Urdu. Toronto had been a melting hub of cultures and, therefore, even when I wasn't speaking in Urdu, I was always overhearing others converse in my native language. Saskatoon was a different case altogether and it was there in my Urdu deprived state that I stumbled upon Coke Studio.

Even though this was three years after the first episode had aired, it couldn't have come at a better time for me. I diligently went through episode after episode taking it all in. I was proud of myself for remembering most of the lyrics of old works; I was blown away by the new tunes and creative fusions.

I moved onto older Pakistani and Indian music and then back to reading poetry. I found Iqbal’s Shikwa and Jawab-e-Shikwa, Ghalib’s Deewan-e-Ghalib and Faiz’s Zindan-nama and gobbled them up much like I had done when I was younger.

Urdu welcomed me back into the fold with both arms wrapped tightly against my insolent self. I could not fathom how or why I had let go of the language that taught me to express myself eloquently.

Much as I loved English, the lack of adjectives and even pronouns was bothersome. There is a well known cliché about how everyone is addressed as 'you' in English but Urdu does the job better for different relationships; 'aap', 'tum' and 'tu' all convey the same meaning, but cannot be used interchangeably.

Urdu poetry is unique. I tried to translate it into English for some of my friends but failed miserably. Therefore, like any zealot, I blamed it on the limitations of the English language. I started teaching my friends Urdu much like I had tried to back in grade six. This required me to write again.

I have to admit that writing again after seven odd years seemed more difficult than I thought. Even though I was regularly reading, it proved harder to put my thoughts into words on paper. I persevered, and much as I would like to say, it has been successful.

I’m still a bit hesitant when it comes to writing and often resorts to second guessing myself. I don't mind one bit; it took me years to realise what I had thrown away and if I had to find my flair back the hard way. It's the least I could do.

The important thing is I learned my lesson and no matter where I go in life from here, Urdu will always be a cherished part of it.

Read more by Nabeel here.

COMMENTS (55)

Comments are moderated and generally will be posted if they are on-topic and not abusive.

For more information, please see our Comments FAQ